WITH almost the entire global economy at a standstill in order to contain the spread of the novel coronavirus, job losses are expected to be significant. The International Labour Organization (ILO) said early this month that 1.25 billion workers around the world, representing 38% of the global workforce, face a high risk of a pay cut or layoff.

Malaysia, now in the sixth week of the Movement Control Order (MCO), is no different, with economists projecting rising unemployment.

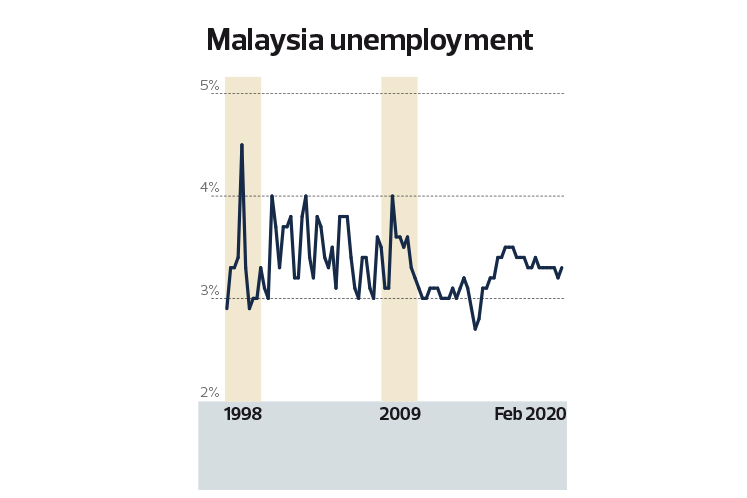

Forecasts of unemployment for this year have been grim, ranging from Bank Negara Malaysia’s 4% and the International Monetary Fund’s 4.9% to as high as 9.2% in a worst-case scenario projected by the Malaysian Institute of Economic Research (MIER).

MIER had on March 23 projected 2.4 million unemployed, before the government revealed the Prihatin and SME stimulus packages. Last Thursday, MIER released its updated numbers showing 1.46 million (or an unemployment rate of 9.2% based on the country’s 15.87 million labour force) under the worst-case scenario.

Under the worst-case scenario, the economy is projected to contract by 1% year on year. It is projected to expand by 3.8% in the best-case scenario.

The latest unemployment data from the Department of Statistics (DoS) shows Malaysia having 525,200 unemployed, or a rate of 3.3%, as at end-February this year.

“When there is an economic crisis, the first to be impacted will be jobs. This crisis is health-related and because the country is under MCO, things cannot move, so more people will be unemployed. The government came up with wage subsidies to help as much as possible but it also depends on how long businesses can hold on,” says Lee Heng Guie, executive director of the Associated Chinese Chambers of Commerce and Industry of Malaysia’s Socio-Economic Research Centre (SERC).

The ILO’s projected 1.2 billion jobs at risk are concentrated in economic sectors that have seen a drastic decline in output, namely accommodation, food services, manufacturing, wholesale and retail trade and real estate and business activities.

“These sectors are labour-intensive and employ millions of often low-paid, low-skilled workers, particularly in the case of accommodation and food services and the retail trade. The economic risks will be felt particularly hard by workers in these sectors,” it says in an April 7 report.

Locally, the DoS’ survey of 168,182 respondents from March 23 to 31 — about a week into the first phase of the MCO — shows a similar trend.

From the survey, the agriculture and services sectors registered the highest percentage of job losses compared with other sectors, at 21.9% and 15% respectively.

Within the agriculture sector, 33% and 21.1% of workers in the fishing and agriculture and plantations sub-sectors respectively, had lost their jobs. In the services sector, the most affected were those in the arts and entertainment with 38% losing jobs, followed by food (35.4%), transport and storage (18.7%), and accommodation (14.6%). (See table for more details.)

S&P Global Ratings, in an April 19 report, says services have been hit hard as activities in this sector often require human-to-human contact while Covid-19 containment measures include social distancing.

“The clash of these two is obvious. Any activity that cannot be done online or by phone will feel the full force of these policies. At the same time, the service sector fuels job growth. This is as true in China as it is in Australia and Japan,” it says, noting that as agricultural jobs disappeared in China and other emerging markets, the workers streamed to hotels, restaurants and shopping malls, instead of factories. Malaysia is no different.

“Malaysia’s industrialisation has created jobs but many more were created in the service sector than manufacturing. We estimate that total employment in Malaysia has grown by about 1% per year since 2000. During this period, industrial jobs grew 0.3% while service sector jobs grew by over 1% per year, more than three times as fast as industry. This is healthy and expected for an economy like Malaysia’s, which is growing richer over time.

“Malaysia’s manufacturing sector, helped by FDI [foreign direct investment] inflows, has become sophisticated and this means it is capital-intensive. Production relies more on complex machines and equipment than it does unskilled workers. The service sector is labour-intensive. Restaurants, shopping malls and hotels rely more on their staff than they do on machines,” the report’s author and S&P’s Asia-Pacific chief economist Shaun Roache tells The Edge.

The growth of the service sector has made it the most important employer in Asia-Pacific and most are small and medium enterprises (SMEs). In Malaysia, SMEs account for 70% of employment.

“The SME sector is crucial to the economy and may need further stimulation. Our proposal is double the RM10 billion stimulus to ensure the retrenchment of workers and closure of businesses is not worse than it is,” said MIER chairman Tan Sri Dr Kamal Salih during a webinar on its national economic outlook for 2020/21 last Thursday.

The employment outlook is looking bleak with 78.7% of companies surveyed by the Federation of Malaysian Manufacturers saying they would have to lay off up to 30% of their employees, 27% indicating they would let go 21% to 30%, and 22% between 11% and 20%. The survey was conducted from April 6 to 10, with 419 companies — mostly from the manufacturing sector — participating.

With MIER looking at 1.46 million unemployed in its worst-case scenario, the survey findings are not surprising and the worst hit are expected to be among the B40 income group.

When asked how bad things could get, Christopher Choong, deputy director of research at Khazanah Research Institute (KRI), prefers to err on the side of caution.

He points to the 47,000 applications for the government’s Employment Retention Programme (ERP) as at April 12 compared with the target of 33,000. As for the Wage Subsidy Programme (WSP), within four days of the application going online, 299,000 applications for employees — or 6.3% of the 4.8 million targeted — had been received.

According to Minister of Finance Datuk Seri Tengku Zafrul Abdul Aziz, as at April 19, WSP applications from 159,000 employers for one million workers have been approved, involving a total subsidy of RM1.2 billion.

Choong points out that these do not include retrenchment numbers from the Employment Insurance System (EIS) as well as those who are self-employed.

“Given all these, I think a 4% to 4.9% unemployment rate could be on the conservative side. Moreover, Bank Negara numbers are based on the assumption of a four-week MCO, which we now know has been extended by another four weeks,” he says.

Implications of high unemployment

High unemployment is bad news, posing myriad problems for the government of the day. S&P Global, which expects unemployment to average 4.3% this year, sees job losses taking a toll on the capacity of households to service loans, given the high ratio of debt-to-GDP in this segment — 82.7% as at end-2019.

“Malaysia’s household debt as a share of gross domestic product is high compared with its global emerging-market economy peer group. Households would find it more difficult to service their debt if they suffer a loss in income, either because they have lost their jobs or are working fewer hours. This could mean that households will spend less on other things, including local goods and services. In turn, this could mean weaker consumption and slower economic growth, which might mean even more job losses,” says Roache.

Deflation, an indication of weak consumption, had already emerged in March with the Consumer Price Index registering a year-on-year decline of 0.2%. UOB Global Economics and Markets Research has forecast full-year deflation at -0.5% for 2020 — marking the first annual deflation since 1969.

The fallout from Covid-19 containment measures will lead the global economy to its worst recession — or what the IMF has labelled the Great Lockdown — since the Great Depression. The IMF expects world output to contract sharply by 3% this year, compared with growth of 2.9% in 2019. A recovery is expected in 2021 with growth projected at 5.8%.

“Much-worse growth outcomes are possible and maybe even likely. This would follow if the pandemic and containment measures last longer, emerging and developing economies are even more severely hit, tight financial conditions persist or if widespread scarring effects emerge due to firm closures and extended unemployment,” says IMF economic counsellor Gita Gopinath in its World Economic Outlook report issued two weeks ago.

MIER’s Kamal cautions that the longer the containment policy lasts, the deeper the recession. However, prematurely ending the containment measures may lead to a second wave of infection, which would also take a toll on the economy. “Containment measures have to be actively monitored,” he said during the webinar.

And, economists warn that jobs lost will not come back easily.

“Demand may be slow to come back, employers may not hire immediately and digitalisation would have an impact on net job creation,” says SERC’s Lee who sees the coming unemployment situation to be more severe than that seen in the recessions of 1985, 1998 and 2009.

“We should be mentally prepared for high unemployment. Don’t forget the new graduates, diploma holders and others will be coming into the market,” he cautions.

KRI’s Choong says that post-MCO, a labour reallocation strategy should be put in place to address high unemployment. The task could be undertaken by the EIS portal as a job matching platform linked to public employment services such as training, career counselling and include other benefits such as ERP and WSP.

“This means that we have a very clear picture of the labour supply side, plus we can even think of opening this up to self-employed workers via their registration with the Self-Employment Social Security Scheme. We can structure this in terms of two programmes: a temporary work programme (especially for workers affected by labour reduction measures but who are still attached to an employer), and a job creation programme (for workers who are retrenched or unemployed),” he says via email.

Choong also calls on public investments to catalyse strategic sectors, given that the private sector would unlikely make the first move to invest owing to the uncertainties in the market.

“Other than the fact that start-up costs would be lower now, there are also opportunities to rethink how we want to reorganise our economy,” he says.

For example, there would be more demand for digital ecosystems in both the public and private sectors — contactless systems, online meetings, remote services and mobile payments. Secondly, disruptions of supply chains translate into the need to minimise waste and optimise material usage, making it a good time to ramp up the recycling and waste management industries. Thirdly, more businesses would be thinking of repurposing workplaces to be nimble and work from home (WFH)-equipped in terms of design, technical support and construction. Lastly, the formal care sector needs to be expanded as the pandemic has shown how important care workers are during this period of lockdown, he says.

Now with the MCO extended by another two weeks, bringing the containment period to six weeks, the unemployment problem is more likely than not to be exacerbated.